|

|

1101-1200

|

|

|

|

5. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Bible]. France. Latin text in early angular gothic script

|

early XIII century

|

32.5 x 23 cm.

|

|

“This translation of the Bible was made by Jerom at the request of Pope Damsus. It was begin in the year 382 A.D. and finished 16 years later. For his great scholarship more than for his eminent sanctity, Jerome was later made a saint. This version of the Bible was his most important work.

“The angular book hand, executed with amazing skill and precision, reflects the spirit of contemporary architecture of the early XIIIth century. Closely spaced perpendicular strokes and angular terminals have supplanted the open and round character of the preceding century. It is a beautiful book hand but exceeding difficult to read.

“The quills used in writing were obtained from the wings of crows, wild geese, and eagles. To keep them sharp and their strokes of uniform width required skill and great sensitivity in hand pressure. It would be difficult to imitate or approximate the fine details even with the special steel lettering pens of today.”

|

|

6. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Cambridge Bible]. England (Cambridge). Latin text in early angular gothic script

|

early XIII century

|

27.5 x 20.5 cm.

|

|

“The only Bible known to Western Europe for the thousand years from 400 to 1400 was this version by St. Jerome. In the early part of the XIIIth century it is almost impossible to distinguish the book hands of France from those of England. The decorative initials, color of ink, and texture of vellum are the clues which aid in assigning provenance, as in this instance. Not many fragments of this age and size are known to have survived the destruction and dispersal of English monastic libraries which was ordered by Henry VIII in the year 1539.

“This small size lettering, seven lines to the inch, is formed with skill and precision that made the XIIIth century noted for the finest calligraphy of all time. To write seven lines to an inch, maintain evenness throughout, and have each letter clear and precise is a great achievement for any scribe, yet in the XIIIth century this was not an exceptional accomplishment.”

|

|

7. Aurora [Aurora]. England. Latin text in early gothic script

|

early XIII century

|

23.5 x 11.5 cm.

|

|

“This famous paraphrase of the Bible in Latin verse was one of the most popular Latin books of poetry of the late XIIth and XIIIth century. Petrus de Riga, who died in 1209, began it. Aegidius of Paris finished it. This version did not appear in printed form until a very late date, despite its popularity. The format of this page, twice as long as it is wide, demonstrates the English custom of folding the skins lengthwise. The practice of settling off by a space the initial letter of each line also helps to give the page an unusual appearance. It is written in a very small script, six lines to an inch, in a hand characteristic of Northern France and England at this period.”

|

|

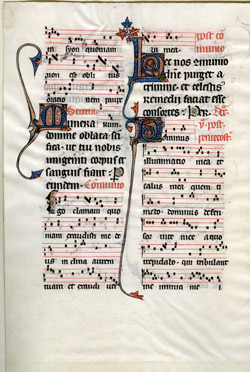

8. Graduale [Gradual]. England. Latin text in early angular gothic script, square Gregorian notation

|

early XIII century

|

18.5 x 12 cm.

|

|

“Graduals are the books containing the chants for the celebration of the mass. English manuscripts of this early date and small size are rare. This volume, with the uncertain strokes in the script, seems to indicate that the transcriber was unaccustomed to writing in this small scale. There are four and five line staves, and the ‘F’ and ‘C’ lines are indicated. Most of the various forms of written notes can be found on each leaf of this book. Those occurring more frequently are punctum (L. punctum, prick), a single note; virga (L. virga, rod), a square note with a thin line attached; podatus (L. pes, foot), two square notes, one above the other; climacus (L. climax, ladder), a virga note with two or more diamond shaped notes. There are other forms for particular nuances of expression.

“There are more than 2,300 chants which have come down to us from the Middle Ages. The majority of these, however, can be reduced to a relatively few melodic types — probably not exceeding fifty in all.”

|

|

9. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Bible]. France (Paris). Latin text in miniscule angular gothic script

|

mid XIII century

|

17 x 12.5 cm.

|

|

“These miniature or portable manuscript copies of the Jerome version of the Bible were nearly all written by the young wandering friars of the newly founded order of Dominicans. With almost superhuman skill and patience, and without the aid of eyeglasses, an amazing number of these small Bibles were produced by writing with quills on uterine vellum or rabbit skins. No plausible reason has yet been advanced for such large scale production. They were used sparingly, as is evidenced by their still fine condition. Few people could afford to buy these volumes, which took the equivalent of two years’ time to transcribe. Still fewer laymen could read or would dare to risk excommunication by the church. Pope Innocent III, some years earlier, had issued an edict forbidding the reading or even the touching of a Bible by persons not belonging to the clergy. The precision and beauty of the text letters and initials executed in so small a scale, twelve lines to an inch, are among the wonders in book history.”

|

|

10. Psalterium [Psalter]. Germany [though possibly England or France?]. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XIII century

|

20 x 14.5 cm., illuminated

|

|

“The line endings of a fish, elongated or shortened as the space required, and the grinning expression on the fish emblem have in some book circles given these German Psalters the nickname ‘Laughing Carp’ Psalters. The fish, as is well known, was one of the earliest and most common symbols from Christ. An early acrostic, IESOUS CHRISTOS THEOU HUIOUS SOTER (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior), is based on the letters in the Greek word for fish, ICHTUS. The lozenge heads on top of many of the vertical pen strokes are characteristic of German manuscripts.”

|

|

11. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Bible]. Italy. Latin text in rotunda gothic script

|

mid XIII century

|

13 x 20 cm., illuminated

|

|

“In 1217, St. Dominic, the founder of the order which bears his name, withdrew from France and settled in Italy. Here, in the next four and last years of his life, he founded sixty more chapters of the Dominican order. Many of the younger members of the order studied at the University of Bologna and, while there, produced a great number of these small portable Bibles, just as did their brothers at the University of Paris in France and the University of Oxford in England.

“There was a difference in the art of the scriptoria in the various countries. In Engladn and France the ideal of craftsmanship was very high, while at this time, in Italy, a rather casual attitude prevailed. In the XIIIth century Italy was distraught by the long struggle between the papal and anti-imperialistic Ghibellines. Little encouragement was given by either party to the arts. This leaf reveals, however, the skill and keen eyesight which were necessary for the writing of ten of these lines to the inch.”

|

|

12. Psalterium [Psalter]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XIII century

|

13.5 x 10 cm., illuminated

|

|

“This small Psalter leaf illustrates the fact that, although skilled scribes were available in many monasteries in the XIIIth century, some of the monks who attempted to apply and burnish the gold leaf were still struggling with many problems of illumination. The famous treatise De Arte Illuminandi and Cennino Cennini’s Trattado were both of later date. These works gave directions on how to prepare and use the glair of egg, Armenian bole, stag-horn glue, and hare’s foot, and on how to burnish the gold with a suitable wolf’s tooth. These books might not have been too helpful, however, for the author of the De Arte Illuminandi adds, ‘Since experience is worth more in all this than written documents, I am not taking any special pains to explain what I mean.'”

|

|

13. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Oxford Bible]. England (Oxford). Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XIII century

|

20 x 14 cm.

|

|

“It is usually difficult to distinguish the miniature or portable Bibles made by the young Dominican friars in England from those written in France. At times the colophon tells us that a book was executed in the Sorbonne, the newly founded school of theology in Paris, or in the University Center at Oxford. The Dominican order was founded in 1216 A.D. and soon spread all over Europe. About 1219 A.D., King Alexander of Scotland met St. Dominic in Paris and persuaded him to send some members of his brotherhood to Scotland. From here they spread to England. The original master text was carelessly transcribed again and again. It may even have been incorrectly copied from the Alcuinian text written for Charlemagne. Therefore, ‘correctories’ had to be made. In the latter part of the XIIIth century, Roger Bacon condemned unsparingly manuscripts which, although they were skillfully and beautifully written, transmitted inaccuracies of text.”

|

|

14. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Bible]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

late XIII century

|

40.5 x 27 cm., illuminated

|

|

“This copy of the Latin version by St. Jerome was made during the period when France stood at the height of her medieval glory. A decade or two before, Louis IX (Saint Louis), the strongest monarch of his age, had made France the mightiest power in Europe. This favorable political situation rendered possible the ‘golden age’ of the manuscript, and Paris became the center in which the finest manuscripts were written and sold.

“In the quarter century from 1275 to 1300, marked advances were effected in the art. The bar borders came to be executed in rich opaque gouache pigments, with ultramarine made of powdered lapis lazuli predominating. The foliage scroll work inside the initial frame created a style that persisted with little or no change for nearly two hundred years. The script was well executed and was without rigidity or tension. All these elements, together with the sparkle which was created by the causal distribution of the burnished gold accents, give to this leaf a striking atmosphere of joyous freedom.”

|

|

15. Missale Bellovacense [Missal]. France (Beauvais). Latin text in transitional gothic script

|

ca.1285

|

29 x 20 cm., illuminated

|

|

“This manuscript, a special gift to a church in the city of Beauvais, was written for Robert de Hangest, a canon, about 1285 A.D. At that time, Beauvais was one of the most important art centers in all Europe, The ornament in this leaf shows the first flowering of Gothic interest in nature. The formal hieratic treatment is here giving way to graceful naturalism. The ivy branch has put forth its first leaves in the history of ornament. The writing, likewise, is departing from its previous rigid character and displays an ornamental pliancy which harmonizes with the decorative initials.”

|

|

16. Breviarium [Breviary]. England. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

ca.1420-1430

|

10.5 x 7 cm., illuminated

|

|

“Breviaries were seldom owned by laymen. They were service books and contained the Psalter with the versicles, responses, collects and lections for Sundays, weekdays, and saints’ days. Other texts could be included. A Breviary, therefore, was lengthy and usually bulky in format. Miniature copies like the one represented by this leaf are rare.

“The angular gothic script required a skilled calligrapher. It would be difficult for a modern engrosser to match, even with steel pens, the exactness and sharpness of these letters formed with a quill by a XIIIth century scribe. Green was a decorative color added to the palette in the late XIIIth century in many scriptoria. The medieval formulae for making it from earth, flowers, berries, and metals are often elaborate and strange. This manuscript was written on fine uterine vellum i.e., the skin of an unborn calf. It evidently had hard use, or many have been buried with its owner.”

|

|

17. Psalterium [Psalter]. England. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

late XIII century

|

17.5 x 11 cm., illuminated

|

|

“Illuminated Psalters occur as early as the VIIIth century, and from the XIth to the beginning of the XIVth century they predominate among illuminated manuscripts. About 1220 A.D., portable manuscript volumes supplanted the huge tomes favored in the preceding century. This change in size caused the creation of a more angular and compact script. In general, smaller initial letters were used, and writing was done in double columns.

“At this time the pendant tails of the initial letters are rigid or only slightly wavy, with a few leaves springing from the ends. Later, they became free scrolls, with luxurious foliage, and were extended into all the margins. The blue and lake (orange-red) color

scheme with accents of white is a carry-over from the Westminster tradition which prevailed in the previous century. The solid line-filling ornaments at the ends of the verses were a new feature added in the second half of the XIIIth century. Silver and alloys of gold are used on this leaf.”

|

|

18. Breviarium [Breviary]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

late XIII century

|

15 x 11.5 cm.

|

|

“The Breviary is one of the six official books used by the Roman Catholic Church in its liturgy. It is a book of prayers for the clergy, giving the directions for all of the various services of the Divine Hours throughout the year. The other five official books are the Pontifical, the Missal, the Ritual, the Martyrology, and the Ceremonial of the Bishops.

“The angular script in this leaf is executed with great skill and precision. The small and vigorous black initials and the hair line details found in many of the ascenders and terminal letters indicate the work of a superior calligrapher, skilled not only in writing but also in sharpening his quill. The initials and the dorsal decorations also represent the same high standard of craftsmanship. Strangely, the rubrications do not show as great a calligraphic skill. Usually it was the task of the superior scribe to insert the rubrics or directions for conducting the service.”

|

|

|

1101-1200

|

|

|

|

19. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Vulgate Bible]. Italy. Latin text in traiditionrotunda script

|

early XIV century

|

23.5 x 17.5 cm.

|

|

“At this period, the St. Jerome Bible was not transcribed as often as one would expect in the country of its origin and the very land which held the seat of the Roman Church. During the greater part of the XIIIth century, while the popes were greatly concerned with gaining political power, art was at a low ebb in Italy, and religious manuscripts were comparatively few and far inferior to the work of monastic scribes in Germany, France, and England. But with the great wealth accumulating in Italy during the XIVth century through commerce and the Crusades, this country soon surpassed in richness as well as in numbers the manuscript output of all other nationalities.

“The rich black lettering of this manuscript is in the transitional rotunda script and is executed with skill and beauty. It is supplemented by initial letters in rich ultramarine blue and deep cinnabar (vermillion), which colors are reflected in the ornament of the Romanesque capitals. All of these factors combine to indicate that the manuscript was executed in Italy, possibly at Florence.”

|

|

20. Psalterium [Psalter]. Netherlands. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

early XIV century

|

13 x 9.5 cm., illuminated

|

|

“Small Psalters of this period are comparatively rare, since Psalters were used primarily in the church services and not by the layman. Here, the letters and ornament still retain all the rigidity of the previous century and give no indication of the rounder type of letter or any beginning of the interest in nature that characterized the work of the scribes in France. The filigree decoration, as well as the line-finishing elements, show, however, more creative freedom than either the initial or the text letters. The small burnished gold letters display considerable skill on the part of the illuminator, for it is difficult to control small designs in the gesso used as a base for the raised gold leaf.”

|

|

21. Hymnarium [Hymnal]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script, Gregorian notation

|

early XIV century

|

16.5 x 11 cm., illuminated

|

|

“At important festival services such as Christmas and Easter these small hymnals were generally used by the laymen as they walked in procession to the various altars. Much of the material incorporated in the hymnals was based on folk melodies. Hymns, like the other chants of the Church, varied according to their place in the liturgy. Their melodies are frequently distinguished by a refrain which was sung at the beginning and at the end of each stanza.

“The initial letter design of this leaf persisted with little or no change for a long period, but the simple pendant spear was used as a distinctive motif for not more than twenty-five years.”

|

|

22. Missale Herbipolense [Missal]. Germany (Wurzburg). Latin text in angular gothic script; transitional early Gothic notation

|

early XIV century

|

36 x 26 cm.

|

|

Scope and content:

“The Missal has been for many centuries one of the most important liturgical books of the Roman Catholic Church. It contains all the directions, in rubrics and texts, necessary for the performance of the mass throughout the year. The text frequently varied considerably according to locality. This particular manuscript was written by Benedictine monks for the Parochial School of St. John the Baptist in Wurzburg shortly after 1300 A.D.

“The musical notation is the rare type which is a transition between the early neumes and the later Gothic or horseshoe nail notation. The ‘C’ line of the staff is indicated by that letter, and the ‘F’ simply by a diamond, an unusual method. The bold initial letters in red and blue and ‘built up’ letters; first the outlines were made with a quill and then afterward the areas were colored with a brush.”

Researchers comments::

Canticles of Zachary (Luke 1:68-79); Annunciation of St. John the Baptist; hymn of Zachary and Elizabeth.

|

|

23. Breviarium [Breviary]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XIV century

|

18 x 12 cm., illuminated

|

|

“In the middle of the XIVth century many of the manuscript show influences from other countries. Illuminators, scribes, and other craftsmen traveled from city to city and even from country to country. While the script of this leaf is almost certainly French, the initial letters and filigree decoration might easily be of Italian workmanship, and the greenish tone of the ink suggest English manufacture. The dorsal motif in the bar ornament is again decidedly French, and the lemon tone of the gold is a third indication of French origin. In England, the burnished gold elements are generally of an orange tint, due to the presence of an alloy; in Italy, they are a rosy color because the underlying gesso or plaster base was mixed with a red pigment.”

|

|

24. Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. England (?). Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XIV century

|

17.5 x 12.5 cm., illuminated

|

|

“This particular Book of Hours, a devotional prayer book for the layman, was made for the use of Sarum, the early name for Salisbury, England. This text was accepted throughout the province of Canterbury. The manuscript was written about the time Chaucer completed his Canterbury Tales, but evidently by a French monk, who might have been attached, as was often case, to an English monastery. Again, the book could have been specially ordered and imported from abroad. The initial letter and the coloring and the treatment of the ivy are unmistakably French.

“The lettering is an excellent example of the then current book hand. There are seven lines of writing to an inch. The words written in red, a heavy color made from mercury and sulphur, show almost the same degree of delicacy as those written with the more fluid ink.”

|

|

26. Missale [Missal]. France (Rouen). Latin text in angular gothic script

|

late XIV century

|

29.5 x 21.5 cm., illuminated

|

|

“The fact that this Missal honors particular saints by its calendar and litany indicates that it was made by friars of the Franciscan order. This was established in 1209 by St. Francis. These wandering friars with their humility, love of nature and men, and their joyous religious fervor, soon became one of the largest orders in Europe.

“This leaf, with its well written, pointed characters and decorative initial letters, has lost some of its pristine beauty, doubtless through occasional exposure to dampness over a period of 600 years. The green tone of the ink is more frequently found in English manuscripts than in French. Howeve4r, the ornament and miniature on the opening page of the manuscript definitely indicate that it is of French origin.”

|

|

|

1401-1500

|

|

|

|

27. Antiphonarium [Antiphonal]. Italy. Latin text in rotunda gothic script, Gregorian notation

|

early XV century

|

33 x 24.5 cm.

|

|

“The chanting of hymns during ecclesiastical rites goes back to the beginning of Christian services. Antiphonal or responsive singing is said to have been introduced in the second century by St. Ignatius of Antioch. According to legend, he had a vision of a heavenly choir singing in honor of the Blessed Trinity in the responsive manner. Many of the more than four hundred antiphons which have survived the centuries are elaborate in their musical structure. They were sung in the medieval church by the first cantor and his assistants. Candle grease stains reveal that this small-sized antiphonal was doubtless carried in processions in dimly lighted cathedrals. In this example the notation is written on the four-line red staff which was in general use by the end of XIIth century. The script is the usual form of Italian rotunda with bold Lombardic initial letters.”

|

|

28. Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. Northern France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

ca.1450

|

15 x 10.5 cm., illuminated

|

|

“This Book of Hours shows definite characteristics of the manuscript art of France and the Netherlands of about 1450 A.D. It was probably one of many copies prepared for sale at a shrine to which devout pilgrims came to worship or to seek a cure. The spiked letters and the detached ornamental bar are unmistakably Flemish in spirit, while the free ivy sprays are distinctively French. The burnished metal in the decorations shows the use of alloyed gold (oro di meta as well as silver.

“Various metals were added in different localities to the fine gold. English illuminations frequently had a decided orange hue, while the French had a lemon cast. The quality of the gold was best enhanced by the use of burnishing tool equipped with an emerald, a topaz, or a ruby. Less successful burnishers contained an agate or the tooth of a wolf, a horse, or a dog.”

|

|

29. Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XV century

|

19 x 13.5 cm., illuminated

|

|

“It is generally no great task to assign these illuminated Books of Hours to a particular country or period. The treatment of the ivy spray with the single line stem and rather sparse foliage is characteristic of the work of the French monastic scribes about the year 1450. The occasional appearance of the strawberry indicates that the illuminating was done by a Benedictine monk. Fifty years earlier the stem would have been wider and colored, and the foliage rich; fifty years later the ivy and holly leaves would entangled with flowers and acanthus foliage.”

|

|

30. Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. France. French text in angular gothic script

|

mid XV century

|

18.5 x 13.5 cm., illuminate

d

|

|

“The text of a Book of Hours consists of Gospels of the Nativity, prayers for the Canonical Hours, the Penitential Psalms, the Litany, and other prayers. The beauty of the rich borders found in some of these books frequently claims our attention more than the text. In these borders it is easy to recognize the ivy leaf and the holly, but is usually more difficult to identify the daisy, thistle, cornbottle, and wild stock. The monks had no hesitancy in letting these flowers grow from a common stem. Because of the translucency of vellum, the flowers, stems, and leaves of the border were carefully superimposed on the reverse side in order to avoid a blurred effect.”

|

|

31. Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XV century

|

19 x 13 cm., illuminated

|

|

“In the second half of the XVth century, the devout and wealthy laymen had a wide selection of Books of Hours from which to choose, both manuscript volumes and printed texts. These were often sold, in large cities, in book stalls erected directly in front of the main entrance to the cathedral.

“The first printed and illustrated Book of Hours appeared in 1486. It was a crude work, but later noted printers such as Verard, Du Pre, Pigouchet, and Kerver issued in great numbers Books of Hours with numerous illustrations and rich borders. The decorations were frequently hand colored and further embellished with touches of gold. These Books of Hours created a strong competition for the more costly manuscript copies.

“Customers who still preferred the manuscript format and could afford it also had a choice of many different types of decoration and could stipulate what quantity and quality of miniatures they desired. By this time the ivy spray had a variety of forms. It might be seen springing from an initial letter, from the end of a detached bar, in a separate panel in company with realistic flowers, or forming a three- or four-sided border intermixed with acanthus leaves and even birds, animals, and hybrid monsters which are neither man nor beat.”

|

|

32. Graduale [Gradual]. Italy (Florence). Latin text in rotunda gothic script, square notations

|

mid XV century

|

26 x 20 cm., illuminated

|

|

“A Gradual contains the appropriate antiphons of a mass sung by the choir of the Latin Church on Sundays and special holidays. The text was furnished largely by the 150 Psalms and the Canticles of the Old and New Testaments. The superb example of calligraphy in this leaf illustrates the supremacy of the Italian scribes of the time over those of the rest of Europe. It is frequently assumed that this late revival of fine writing may have been caused by the concern of scribes over the impending competition with the newly invented art of printing. The music staff still retains here the early XIIth century form with the C-line colored yellow and the F-line red. The four-line red staff had been in use for over two centuries before this manuscript was written.”

|

|

33. Missale [Missal]. Germany. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XV century

|

37 x 28 cm.

|

|

“The Missal, written for the convenience of the priests, combined the separate books formerly used in different parts of the service; namely, the Oratorium, Lectionarium, Evangeliarium, Canon, and others. Gutenberg, who printed his famous First Bible about the time this manuscript was written, based his type designs on a contemporary book hand similar to this example. The craftsmen who created this manuscript had the difficult problem of evolving a harmonious page with two sizes of writing, inserted rubrics, and large and small colored initials. The smaller writing is used for the Orationes, the Psalms, the Secreta, and other parts of the service; the large script for the Sequentia.”

|

|

34. Psalterium [Psalter]. France. Latin text in rotunda book hand, square notations

|

mid XV century

|

39 x 28.5 cm.

|

|

“This Psalter was written by Carthusian monks. Of all the orders the Carthusian was the smallest and most austere. The membership never exceeded one per cent of those enrolled in the combined monastic orders. The Carthusians were frequently hermits, and manuscripts written by them are rare.

“The rotunda book hand used in this leaf is representative of the general excellence maintained by Italian scribes at the time when printing was being introduced into their country. The simple melody for the Psalms apparently was added as a somewhat later date. Close observation of the initial letters will frequently reveal a small black letter inserted as a guide for the monk who later added the colored initial. The use of two guide lines for the lettering is unusual. Ordinarily one line, below the writing, was deemed sufficient. The lines were drawn with a stylus composed of two parts lead and one part tin.”

|

|

35. Jerome, Saint, d. 419 or 20, Sanctus Hieronymus, Contra Jovinianum [Writings of Saint Jerome]. France. Latin text in lettre de somme

|

mid XV century

|

38.5 x 28 cm., illuminated

|

|

“Jerome, the father of the Latin Church and translator of the Bible, shows in his writings his active participation in the controversies of his day (c.332 to 420 A.D.). With the frequent use of vehement invective, he is often as biting as Juvenal or Martial.

“This fine book hand, lettre de somme, obtained its name from the fact that Fust and Schoeffer used a type based on it for the printing of their Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas in 1467. It was the favorite manuscript book hand in the second half of the XVth century for the transcribing of French chronicles and romances. Simplicity and dignity are maintained by omitting all enrichment around the burnished gold letters. The first printed books followed the practice seen here of marking off by hand with a stroke of red the capitals at the beginning of each sentence.

“Fifteenth century ink frequently had a tendency to fade to a gray tone as in this example.”

|

|

36. Horae Beatae M

ariae Virginis [book of Hours]. France. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XV century

|

10.5 x 7 cm.; illuminated

|

|

“Books of Hours, beautifully written, enriched with burnished gold initials, and adorned with miniature paintings, were frequently the most treasured possessions of the devout and wealthy layman. They were not only carried to chapel but were often kept at the bedside at night. Oaths were sworn on them. Books of this small size, two and one-half by three and one-half inches, are comparatively rare. The craftsmanship in this example imitates and equals that in a volume of ordinary size, about five by seven inches. Recently these small ‘pocket’ editions have been given the nickname ‘baby manuscripts.’ In general, the miniature Books of Hours contain only that section of the complete volume which deals with the prayers to be read or recited at the canonical hours; namely, matins, vespers, nocturns, and those for the prime, tierce, sext, nones, and complin. Indulgences were often granted for the faithful reading or recitation of these prayers.”

|

|

37. Epistolarium [Epistolary]. Italy. Latin text in rotunda or round gothic script, square rhetorical neumes

|

mid XV century

|

29 x 22 cm.

|

|

“Epistolaries are among the rarest of liturgical manuscripts. Their text consists of the Epistles and Gospels with lessons from the Old Testament for particular occasions. Sometimes, as in this leaf, they had interlinear neumes in red to assist the deacon or sub-deacon in chanting parts of this section of the church service while he was standing on the second step in front of the altar.

This text is written in well executedrotunda gothic script with bold Lombardic initials. Some of the filigree decoration which surrounds the initial letters has faded because it was executed in some of the fugitive colors which were then prepared from the juices of such flowers and plants as turmeric, saffron, lilies, and prugnameroli (buckwheat thorn berries).”

|

|

38. Missale Lemovicense Castrense [Missal]. France (Limoges). Latin text in angular gothic script

|

mid XV century

|

31 x 24 cm.

|

|

“The provenance of this manuscript is clearly designated as Limgoes because of the inclusion of certain parts of the masses proper to this diocese, and because of the presence of the coat of arms and obituary records of the noted de Rupe family of that city. Frequently, without such data, it would be impossible to determine whether a fragment written in this period and country was from Amiens, Dijon, or Limoges. The national book hand had become amazingly uniform. In this manuscript as in many manuscripts of the XVth century there is an increasing tendency to speed and slackness. France was no longer setting the standard for manuscripts. This example shows that they were greatly influenced by contemporary Italian manuscripts.”

|

|

39. Livy, T. Livii Urbe Condita Libri [History of Rome]. Italy. Latin text in humanistic script

|

mid XV century

|

22 x 16 cm.

|

|

“The known part of Livy’s great life work, the History of Rome, was completed about the year 9 A.D. The finished work consisted of one hundred and forty-two books, of which only thirty-five are extant. These books are regarded as one of the most precious remains of Latin literature.

“One of the outstanding characteristics of the scholars and scribes of the Italian Renaissance was their great interest in Latin literature. Through their influence, many copies of the classics were made from the few IXth and Xth century manuscripts available. These earlier manuscripts had been written in a Carolingian or pre-gothic script to which the XVth century humanistic calligraphers assigned the name antique littera. The letters were not really of antiquity, since miniscule letters were not known before the time of Charlemagne. In the XVth century, this Carolingian script became the inspiration not only for manuscripts like this leaf, but also, shortly thereafter, for the fine roman types designed by the printers in Italy.”

Researcher’s note

Copied by Jacopo Carlo, probably in Genoa, ca.1440.

|

|

40. Aquinas, Thomas, Super primo libro sententarium [Commentary on the Sentences]. Italy. Latin text in humanistic book hand

|

late XV century

|

29 x 21 cm.

|

|

“This text on the Sententiae of Peter Lombard by St. Thomas Aquinas, the ‘Angelic Doctor,’ was the forerunner of the latter’s great work Summa Theologica. It is most unusual to find the writings of a Church Father presented in a humanistic book hand. Some of the humanists called this form of writing antiqua littera, with reference to the Carolingian script, which they mistook for that of antiquity. In this humanistic script, fusion disappeared, letters became more simple, and shading decreased. The first more or less humanistic type of writing appeared in Florence about 1400 A.D.”

|

|

41. Gregory I, Pope, ca.540-604, S. Gregorius Magnus, Dialogi [Dialogues of Gregory the Great]. France. Latin text in lettre batarde

|

late XV century

|

30.5 x 22.5 cm.

|

|

“This composite text includes the Dialogues of Pope Gregory I (St. Gregory the Greaty, 540-604 A.D.), which are largely autobiographical, and his writings on the lives and miracles of the early Italian Church Fathers. The book hand is known as lettre batarde, a semy-cursive hand closely related to the everyday writing used by the people. Many French and Flemish printing types were based on similar batarde hands. The writing was done with comparative speed; the even tone and the exact alignment of the right hand margin, as well as the beauty of individual letters, are admirable. The long ascenders in the upper line were borrowed from the legal documents of that day. Many printers followed the practice shown here

of emphasizing the tone of the first word or two in the beginning of a paragraph. It was usually done without varying the style of the letters, while here we see angular gother used in the first third of the line, followed by the batarde script.”

|

|

42. Psalterium [Psalter]. Germany (Wurzburg). Latin text in angular gothic script, gothic notation

|

1499

|

47.5 x 33.5 cm.

|

|

“This leaf from the Book of Psalms was written in the Benedictine monastery of St. Stephan in Wurzburg and dated 1499 A.D. The book hand closely resembles the fine early gother types called lettre de forme and used by Fust and Schoeffer in their superb Psalter issued in 1457. It is known that these printers also used this type to print the Canon of the mass which was frequently sold as a replacement for the soiled and worn our manuscript pages of that text.

“A close examination indicates that the scribe apparently tried to imitate printing type characters in many instances. In just the same way, the first printers had copied in their designs the current local book hand. The line of music giving the ‘free’ melody of the psalm here retains the early XIIth century staff, with the C-line colored yellow and F-line red. These note forms are frequently called Hufnagelschrift or horse-show nail notation because of their resemblance to hobnails.”

|

|

43. Horae Beate Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. Netherlands. Latin text in bold angular gothic script

|

late XV century

|

18 x 13 cm.

|

|

“In general, the Books of Hours produced for the devout layman in the Netherlands at the end of the XVth century were written in Dutch. This particular example, however, is in Latin. The heavy, angular, and closely spaced vertical strokes, with very short ascenders and descenders, give a much darker tone to the page than do similar scripts in such northern countries as Germany and England. This book hand resembles very closely the types known as lettre de forme which were used by certain anonymous contemporary printers in the Netherlands between 1470 and 1500 A.D.”

|

|

44. Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata [Vulgate Bible]. Germany. Latin text in semi-gothic script

|

late XV century

|

41.5 x 27.5 cm.

|

|

“The Vulgate Bible, a translation credited to St. Jerome, was adopted by the Catholic Church as the authorized version. The leaf was written in Germany nearly sixty years after the invention of printing by movable type. Its semi-gothic book hand is very similar to the type-faces used by the early printers. The number contractions and marks of abbreviation have been inserted boldly, but the little strokes which were added to help identify the letters i and u are barely visible.

“The new art of printing of concerned itself at once with the printing of Bibles of folio size, in Latin as well as the vernacular. In Germany, prior to the discovery of America, twelve printed editions of the Bible appeared in the German language and many others in Latin. An oversupply developed, and more than one printer of Bibles was forced into bankruptcy.”

|

|

45. Horae Beate Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. France. Latin text in gothic script

|

late XV century

|

19 x 13.5 cm.; illuminated

|

|

“This manuscript leaf came from a Book of Hours, sold probably at one of the famous shrines to which wealthy laymen made pilgrimages. To meet the demand for these books, the monastic as well as the secular scribes produced them in great numbers. The freely drawn, indefinite buds here entirely supplant the ivy, fruits, and realistic wayside flowers which characterized the borders of manuscript of the preceding half century. The initial letters of burnished gold on a background of old rose and blue with delicate white line decorations maintain the tradition of the earlier period. The vellum is of silk-like quality that often distinguished the manuscripts of France and Italy.”

|

|

46. Horae Beate Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. Northern France. Latin text in gothic script

|

ca.1475

|

13.5 x 17.5 cm.; illuminated

|

|

“The Book of Hours, the prayer book of the laity, usually contains 16 sections. The section on prayers to the Virgin is the most important and most used, and its manuscripts exceed in number all other XVth century religious texts. The laymen who ordered and purchased these books would at times stipulate the style of ornament and the amount of burnished gold to be used, and could even to a certain extent, select the saints they esteemed most and wished to glorify. In this example, the border reveals by its wayside flowers entangled with the heavy acanthus motif of the North and by the ‘wash’ gold that it was executed in Northern France about 1475 A.D.”

|

|

47. Horae Beate Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. Netherlands. Latin text in angular gothic script

|

late XV century

|

13.5 x 18 cm.; illuminated

|

|

“In assigning this lead from a Book of Hours to the Netherlands it must be remembered that some sections of that country were once part of France, while others belonged to what is now Germany. In this leaf French characteristics predominate, but in no other country did the study of nature have a more direct influence on miniatures and ornamentation than in the Netherlands. Carnations, pansies, columbines, and many other flowers were faultlessly and realistically drawn. A few decades later, at the turn of the century, cast shadows as well as snails, butterflies, and birds were added, with the result that the borders became a distraction to the reader.”

|

|

48. Horae Beate Mariae Virginis [Book of Hours]. Netherlands. Latin text in lettre de France

|

late XV century

|

17 x 12 cm.; illuminated

|

|

“In the XVth century Books of Hours were as much in demand in the Netherlands as they were in France and England. In many of these books it is difficult to distinguish the Dutch Hours from those of Northern France or the Rhineland. In the middle of the century this whole area was interested in naturalism and made its illustrations so vivid that sometimes they approached those of our seed catalogues. It is not difficult to recognize carnations, pansies, columbines, and strawberries. The style later became even more realistic when the naturalistic flowers were painted with cast shadows. When such flowery decorations are found on a rather heavy piece of vellum, entangled with the swirling acanthus leaf and accompanied by a heavy lettre de forme script, one can be fairly safe in assigning the leaf to the province of Brabant. It was a difficult technical achievement at this time to apply the gouache colors to gold leaf so that they would adhere without flaking.”

|