Beth Hapgood Papers

Daughter of a writer and diplomat, and graduate of Wellesley College, Beth Hapgood has been a spiritual seeker for much of her life. Her interests have led her to become an expert in graphology, a student in the Arcane School, an instructor at Greenfield Community College, and a lecturer on a variety of topics in spiritual growth. Beginning in the mid-1960s, Hapgood befriended Michael Metelica, the central figure in the Brotherhood of the Spirit (the largest commune in the eastern states during the early 1970s) as well as Elwood Babbitt, a trance medium, and remained close to both until their deaths.

The Hapgood Papers contain a wealth of material relating to the Brotherhood of the Spirit and the Renaissance Community, Metelica, Babbitt, and other of Hapgood’s varied interests, as well as 4.25 linear feet of material relating to the Hapgood family.

Background on Beth Hapgood

A self-described “observer,” spiritual seeker, historian, and writer, Beth Hapgood was born in Hanover, New Hampshire, during the height of the great influenza epidemic of 1918, the first of three children in a family of intellectuals and writers. Her father Norman Hapgood, was a diplomat under Woodrow Wilson and a prominent editor of magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar and the Christian Register. Her mother Elizabeth (Reynolds) was one of the first female professors at Dartmouth, a linguist who was instrumental in establishing the Russian department and who served as a translator for the legendary Russian acting teacher Constantin Stanislavki. Talent flourished elsewhere in Hapgood veins as well. Beth’s uncle Hutchins Hapgood was a well-known writer who co-founded the Provincetown Players, a politically-active theatre group on Cape Cod, with his wife Neith Boyce. Another uncle, William Powers Hapgood, founded the Columbia Conserve Company, worker-owned a cannery in Indiana that is nationally recognized as an innovative experiment in workplace democracy.

As a child, Beth enjoyed a privileged life, traveling throughout Europe with her parents as they pursued various literary and diplomatic projects. However, after Norman’s death from complications of pneumonia in 1937, Elizabeth found it difficult to travel so extensively with her three growing children. Following a final trip to Russia to visit Stanislavski, she brought her family back to the United States where they divided their time between homes in New York City and Petersham, Massachusetts.

Beth credits her upbringing in New York with making her a “seeker.” She recalls being engrossed by the endless variety of people encountered during her long walks through the city, and although she was a quiet student, she remembers a teacher reassuring her that “still waters run deep.” Through the influence of her mother, Hapgood became convinced at a young age that women are capable of being whatever they want to be. She carried this realization with her to Wellesley College, from which she graduated in 1940 with a degree in sociology, and through her masters degree in psychology at Farleigh-Dickinson University. Always fascinated with understanding the thoughts and motives of others and how people communicate, she chose to study graphology, the science of handwriting analysis. Her thesis, the first academic study of handwriting analysis in the United States, led to a successful career in graphology, spawning a weekly newspaper column and numerous articles and conference papers.

At one of these graphology conferences, Hapgood met Bob St. Clair, with whom she fell in love and, against the wishes of her family, married in 1940. She described St. Clair as a “blue-eyed grasshopper” for his inability to stick to one job, and for the first several years of their marriage, the family moved around with remarkable regularity. Before settling in Northfield, Mass. in 1952, the Hapgoods passed through Virginia, Maryland, Long Island, New York City, and Maine, all the while their family grew to include six children: Amy, Steven, Eva, Bea-Beth, Jon, and Tina. In Northfield, the St. Clairs purchased a youth hostel at 88 Main Street, a rambling house that had been one of the first youth hostels in the nation. Despite the demands of her young family, Beth afforded herself the opportunity to spend time in the hostel and listen in on the travelers’ conversations, the constant ebb and flow of people through the hostel fit perfectly with her ideas about a global human family that was infinitely interconnected. By 1956, though, the responsibilities of running an active hostel grew too great, leading the St. Clairs to close down that portion of the house.

In 1963, she found a new opportunity to explore the philosophical and spiritual questions that had always occupied her by accepting a position teaching psychology and sociology at Greenfield Community College (GCC). A key event in her spiritual development came in 1969 when she was introduced to a local trance medium, Elwood Babbitt, by her maverick cousin, Charles Hapgood. Although fourteen years her senior, Charles and Beth enjoyed a close relationship founded on their equally unorthodox view of life and pursuit of a deeper understanding of personal relation and in Elwood, both found a close friend and inspiration. Clairvoyant from his youth, Babbitt had developed his psychic abilities at the Edgar Cayce Institute, and by the mid-1960s, was well known locally through his readings and lectures, often opening his home to other seekers. Charles, a professor at Keene State College, had worked closely with Babbitt studying the physical effects of the medium’s trance lectures, and by 1967, he began to take on the painstaking process of transcribing and copying them. With communications purporting to come from Jesus, Albert Einstein, Mark Twain, and the Hindu god Vishnu, among others, these lectures formed the basis for several books by Hapgood and Babbitt, including Voices of Spirit (1975) and Talks with Christ (1981). Like her cousin, Beth worked closely with Babbitt, establishing a non-profit, alternative school, the Opie Mountain Citadel, which was essentially run out of Babbitt’s home in Northfield.

1968 was a pivotal year for Hapgood, who was not immune to the social changes sweeping the nation. In that year, her marriage dissolved and health problems forced her to take leave from her teaching responsibilities at GCC , leaving her to question whether she should could her home. Although the hostel at 88 Main Street had officially shut down years previously, the tide of young people coming through Hapgood’s life never slowed. Many came into her life through her children, and many seemed to be seeking an emotional safe haven from what Hapgood calls “(the) chaotic times, when the shattering of basic trust and order went way beyond the smashing of an atom.” Whatever it was that initially drew so many young people to Western Massachusetts, these travelers would have a lasting impact on Hapgood and her family.

Among all the young people drawn to Hapgood in the mid-1960s, Michael Metelica stands out. Metelica first appeared at 88 Main Street as a sixteen year old in 1966, a friend of Hapgood’s daughter Eva. From the beginning, he and Beth developed a close bond, remaining in contact when Metelica dropped out of school and traveled to San Francisco in 1966 to join the Hells Angels and take part in the cultural revolution shaking the Haight Ashbury district. She was there to greet him when he returned to his home in Leyden, Mass., two years later, burned out and disillusioned. Looking for an alternative way of living, Metelica moved into a treehouse in June 1968, joined shortly by eight of his friends. Almost immediately, others were drawn to the group who dubbed themselves the Brotherhood of the Spirit, forming the core of what would eventually become the largest commune in the eastern United States.

In rural Leyden, local reaction to the Brotherhood was decidedly mixed, and after the treehouse was burned in August 1968, the members built a shack to replace it. In the next year and half, the group moved several times, settling for a short time in Charlemont, Mass., in Guilford, Vermont, and Heath, Mass., before purchasing 25 acres in Warwick, not far from Babbitt’s house. The early days of the Brotherhood were full of ideas and growth. The early members wholeheartedly embraced the sixties ethos by dropping out of the mainstream to rethink the values with which they had been raised and proclaiming that they were an “unintentional community,” a group of peers without hierarchy or leadership who shared all in common. Drawn largely from the working class, rather than their middle class roots, the early members created a commune with a distinctive tenor. Although early on the Brotherhood adopted a strict policy of no drugs, alcohol, violence, or promiscuity, as the commune grew, it became increasingly clear that they would be unable to monitor every individual. By 1970, the Brotherhood was hosting over a hundred visitors a day in addition to the seventy permanent members, and particularly among the transients, many of the excesses of the sixties became commonplace. Coming from all across the country, the crush of visitors made it difficult to maintain the unity of vision and increasingly, an inner circle of original members assumed greater authority.

In 1970, Babbitt entered the scene at the Brotherhood and soon became a sort of “spiritual mentor” to the community, teaching Metelica how to develop his psychic abilities. With his charismatic personality, Metelica had little trouble taking on the role of spiritual leader, as he had community leader, even though he was barely in his twenties. By late in the summer, Metelica began to channel higher spirits on his own, claiming to be the reincarnation of St. Peter and Robert E. Lee. Several members of the Brotherhood credited him with helping initiate a “spiritual renaissance” within the community and with revealing a “purpose in life.” But life in the Brotherhood was not without conflict. Adding to the hard labor of raising their own food and caring for the property were regular complaints about the quantity and quality of food. While members aspired to live truly communally by taking odd jobs in the area and signing over their income to the group, Metelica took the primary responsible for distributing the funds. Particularly in later years, many members felt that Metelica’s generosity toward favored members of the commune was matched with miserliness toward others, an affront to the commune’s stated egalitarian principles. Using communal funds, he relentlessly pursued a musical career. The commune’s band, Spirit in Flesh, formed in 1970, spared no expense on equipment, touring, recording, or advertising, and in at least a limited way, Metelica earned the adulation and other trappings of a rock star’s life.

Meanwhile, Hapgood, whose marriage to Bob St. Clair had ended and health was failing, was still looking to sell her home on 88 Main Street. Seeing that many of the visitors to the Brotherhood were forced to sleep outside in the cold, she decided to sign over the deed to 88 Main Street to the Brotherhood, whom she viewed not only as sharing her spiritual outlook, but as “reaching out with a strong and radiant faith to help other young people toward true spiritual awareness and affirmation of life.” 88 Main soon became the headquarters for the inner circle of the Brotherhood who, as Hapgood later wrote, descended “like a swarm of locusts,” forcing her and her family out. Despite this, Hapgood continued her relationship with Metelica, even as her involvement with the commune diminished.

Local opposition to the Brotherhood, a constant from the Leyden days, reached a crisis point in 1972, in part due to Metelica himself. The revelation that many members had signed up for welfare checks piqued local ire, and the fact that Metelica had required members to sign over their assets while he could be seen driving expensive cars added fuel to the generic mistrust of the community’s esoteric beliefs. Metelica’s increasingly erratic behavior and drug and alcohol abuse became points of further contention, both between the Brotherhood and the local community and within the Brotherhood itself. Metelica responded to the tensions by dissolving the Brotherhood in 1973, forming in its stead a for-profit corporation that he called Metelica’s Aquarian Concept. Changing his name to Rapunzel, Metelica required members to apply for admission to the Concept, promise to take jobs and sign over their full income. Spirit in Flesh was later rechristened Rapunzel, and the members of the commune embarked on a diverse series of commercial enterprises, including a highly successful greeting card company, Renaissance Greeting Cards, a music store, bus service, vegetarian restaurant, and pizza shop.

In 1974, the Aquarian Concept was renamed Renaissance Community to signify the commune’s rebirth. At the time, membership numbered in the hundreds, and as individual members began working and earning their own money, many became even less willing to accept the hierarchy that had developed. Several members came even to question Metelica’s sanity and ability to run the commune. In 1975, the house in Warwick had become so dilapidated that it was virtually uninhabitable, and commune members began fanning out to other Brotherhood owned properties in western Massachusetts. By 1978, one faction came into full rebellion against Metelica, who, for all intents and purposes, had ceased to be any kind of spiritual leader as he focused almost exclusively on his band and a few select members. Babbitt’s interaction with the commune also came to an end after a falling out with Metelica. In 1981, a faction associated with Renaissance Greeting Cards officially split and moved their operations to Maine (where they have continued to prosper). Life in the Renaissance Community became increasingly tense as Metelica was drawn increasingly to a life of drugs, guns, and motorcycles. In a particularly telling instance, his proposal to build a shooting range on the property caused at least one longtime member to leave the community. Despite drug use and financial mismanagement, Metelica remained on the commune off and on until 1988, when the remaining members paid him $20,000 to leave.

Though ousted from her home in Northfield, Hapgood continued on her quest for spiritual enlightenment. At the same time she signed ownership of 88 Main Street over to the Brotherhood, Hapgood officially resigned from GCC, explaining in her letter of resignation that her “first and primary commitment is to the inmost Spirit of the Universe.” After seriously considering a career in the ministry, she married Bob Backman, a graphologist and founder of H.A.R.L. (Handwriting Analysis Research Library), one of the only graphology libraries in the country, and the couple moved to Peace Valley Farm in Royalston, Massachusetts. From there, Hapgood organized workshops and courses on a variety of subjects, including graphology, parenting, and grief counseling. In the mid-1970s she established One World Fellowship, a spiritual group that held regular meetings, published newsletters, and sponsored various events with spiritual focus. Ultimately, One World Fellowship became Hapgood’s own publishing company.

The spiritual quest led Hapgood down several new paths during the 1970s, taking her into the Arcane School and the Findhorn Community in Scotland. Although she never held any official position in the Arcane School, an esoteric organization devoted to spiritual enlightenment, Hapgood was energetic in corresponding with other students, answering their responses to monthly reports on their spiritual progress, and writing lectures that were distributed among her peers. From 1978 to 1980, she lived at the Findhorn Community, a community dedicated to spiritual education and the transformation of human consciousness. All the while, Hapgood kept up a furious pace in writing letters and essays, and continued to teach and work closely with the GCC community through the International Students Program, the Opportunity Center, Campus Free College, and the International Students Program.

The Renaissance Community has survived in Warwick, although membership is considerably lower and individuals now own their own property. Metelica eventually moved to Cairo, New York, where he was diagnosed with cancer. He remained in contact with Hapgood and, in 2002, attended a service held in his honor at Hapgood’s house that was attended by former Brotherhood members. Although the animosities of the past had not been fully rectified by time of Metelica’s death in 2003, many of the members cite this gathering as being a positive and healing experience. Elwood Babbitt passed away in 2001. As of 2005, Hapgood resides in Greenfield and continues her prodigious correspondence and writing projects.

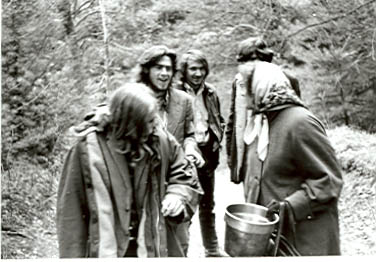

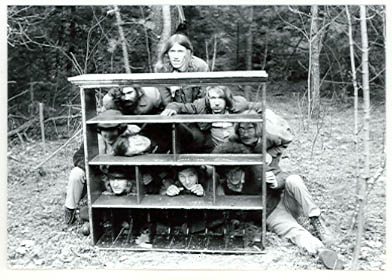

Members of the Brotherhood of the Spirit.

Throughout her life, Beth Hapgood has been an observer standing near the center of social change. Whether it was the largest commune in New England emerging from her kitchen table or her friendship with Elwood Babbitt, who channeled Vishnu in her living room, it is difficult to argue that Hapgood’s life has been a maelstrom of people, ideas, history, spirituality, and hard work. Hapgood’s collection documents many facets of the alternative history of western Massachusetts from the 1950s through the 1980s and the varied people who came through her life. Her connection with emerging new thought and ways of living are well represented in the collection. This self-imposed responsibility to record the events and lives of the people around her has resulted in a diverse and comprehensive collection that spans over a century. From the history of the Hapgood family to the Brotherhood of the Spirit, Hapgood’s collection documents the life of a woman who considered herself not only an observer but the memory of several generations of family, friends, and fellow human beings.

The Hapgood collection contains correspondence, diaries, e-mails, oral and written histories, poetry, newspaper clippings, tapes and transcripts of Babbitt’s trance lectures, legal records, photographs, and a variety of printed materials that give flesh to Beth Hapgood’s evolving interests in graphology and spiritual development, as well as her association with Michael Metelica and the Brotherhood of the Spirit commune. The collection also includes some genealogical material on the Hapgood family, family and town histories, miscellaneous books, welfare reports from the town of Greenfield, book and meeting notes, business and legal correspondence, a memorial scrapbook, various manuscripts, and information pertaining to Opie Mountain and One World Fellowship.

This collection is organized into ten series:

- Series 1. Brotherhood of the Spirit, 1968-2005

- Series 2. Elwood Babbitt, 1967-2003

- Series 3. Correspondence, 1969-2004

- Series 4. Writings by Beth Hapgood, 1932-2002

- Series 5. Teaching, 1959-2004

- Series 6. Spiritual Organizations, 1968-2002

- Series 7. Personal, 1933-2003

- Series 8. Hapgood Family, 1789-2004

- Series 9. Audio Visual, 1938-2002

- Series 10. Newspaper Clippings, 1970-2003

Acquired from Beth Hapgood, July-December 2005.

Processed by Dominique Tremblay, December 2005.

Manuscript Material:

- The Papers of Charles Hapgood, Beth’s cousin, are located in SCUA (MS 445). Additional Hapgood Family material can be found at the Beinecke Library, Yale University (MS 41 and MS 795).

Printed Material:

- The following published materials from the Beth Hapgood Collection are cataloged separately:

- Unidentified. Ankh: Gift Consummate. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, undated.

- A.L.O.E. The Silver Casket or The World and Its Wiles. New York: Robert Carter and Brothers, 1864.

- Armellino, Joseph H. ou Don’t Know Me: Biography of Elwood BabbittY. Turners Falls, Massachusetts: Fine Line Books, 1991.

- Babbitt, Elwood and Charles Hapgood. The God Within: A Testament of Vishnu. Turners Falls, Massachusetts: Threshold Books, 1982.

- Babbitt, Elwood. Perfect Health. Needham, Massachusetts: Channel One Communications, Inc., 1993. Inscribed by Elwood Babbitt.

- Bailey, Alice. The Labours of Hercules. New York: Lucis Publishing Company, 1974.

- Bayley, Beatrice. The Hapgood Family Heritage Book. Beatrice Bayley, Inc., 1981.

- Boyce, Neith. Harry [A Portrait]. New York: Thomas Seltzer, 1923.

- Eliot, George. Romola, v.1. New York: The Mershon Company, undated.

- Groutt, John Walsh. Communal Ideology and Myth: Interpreted Within the Framework of Personal Construct Theory. Dissertation, Temple University, 1973.

- Hapgood, Beth: 88 Main Street: Crossing the Threshold. Greenfield, Massachusetts: Elizabeth Hapgood, 1993. Two editions.

- Hapgood, Beth. The Adventures of Aroma, the Wood Pussy. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, 1986.

- Hapgood, Beth. Amsel: An Album of Memories. Greenfield, Massachusetts: Elizabeth Hapgood, 1993.

- Hapgood, Beth. Beyond Musings: From Benie’s Notebook. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, undated.

- Hapgood, Beth. Dandelion Seeds: Our Poems. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, 1987.

- Hapgood, Beth (editor). Dare the Vision and Endure. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, 1997. Two editions.

- Hapgood, Beth. Fire Weed Flowers: Voices from the Roadside. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, two editions, 1984, 1991.

- Hapgood, Beth. Grains of Sand: A Handful of Poems. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, 1985.

- Hapgood, Beth. Musings from Benie’s Notebook. Greenfield, Massachusetts: Elizabeth Hapgood, c. 1985.

- Hapgood, Beth. Quest for Light. Greenfield, Massachusetts: Elizabeth Hapgood, c. 1990.

- Hapgood, Beth. Tidal Wave in Our Time. Greenfield, Massachusetts: Elizabeth Hapgood, 1993.

- Hapgood, Beth. Walking in the Rain: Poetic Prisms. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, c. 1992.

- Hapgood, Charles. Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings. Revised edition. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979.

- Hapgood, Charles. Talks with Christ and His Teachers. Turners Falls, Massachusetts: Threshold Books, 1981. Two copies, one is inscribed to Beth Hapgood, the other is Charles Hapgood’s personal copy.

- Hapgood, Charles. Voices of Spirit: Through the Psychic Experience of Elwood Babbitt. New York: Delacorte Press, 1975. Inscribed by Elwood Babbitt.

- Hapgood, Elizabeth Reynolds. From the North Porch: A Poetry Journal of Elizabeth. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, 1982.

- Krasnow, Michael Arthur. Ideology and Praxis: Social Processes in a Charismatic Association. Dissertation, Univ. of Massachusetts, 1973.

- Marcaccio, Michael Dennis. The Earnest Brothers: A Biography of Norman, Hutchins, and William P. Hapgood. Diss. Univ. of Virginia, 1972.

- Marcaccio, Michael Dennis. The Hapgoods: Three Earnest Brothers. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977. Published revision of the author’s 1972 Univ. of Virginia dissertation.

- Mikhailusenko, Igor. Poems for Peace. Translated by Walter May, compiled and edited by Beth Hapgood. Greenfield, Massachusetts: One World Fellowship Publications, c. 1988.

- Sammartino, Claudia F. The Northfield Mountain Interpreter. Berlin, Connecticut: Northeast Utilities, 1981.

- Shaw, Arthur. Excellence and Opportunity: The Story of Greenfield Community College 1962-1987. Athol, Massachusetts: Millers River Publishing Co., 1987.

- Stanislavski, Constantin. An Actor Prepares. Translated by Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood. New York: Routledge, 1989.

- Voinov, Nicholas. The Waif. New York: Pantheon Books, 1955.

- Wood, James Rev. Dictionary of Quotations. London: Frederick Warne and Co., 1893.

Cite as: Beth Hapgood Papers (MS 434). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.