Courtesy of Amherst College Special Collections.

Science fiction's meteoric rise was as much about changes in Americans' economic conditions and reading habits as about the cultural climate of the 1950s. The end of the war inaugurated a new era of material prosperity for many Americans, and the middle class swelled to unprecedented size. Americans found themselves with more spending money; this helped usher in a new mass consumerism. At the same time, the war years had changed the publishing industry. During the war American servicemen and civilians alike were wildly enthusiastic about cheap paperbacks printed on government orders and distributed free at military bases. (These were called the Armed Services Editions.) This demand demonstrated to book publishers that paperbacks could be profitable, if they were marketed to a mass audience. The end of wartime rationing made printing those paperbacks possible. Economic conditions were ripe for a paperback explosion.

FDR signed into law the Serviceman's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly called the "G.I. Bill." The bill provided home loans, business loans, unemployment compensation, and educational/vocational training for millions of servicemen returning from WWII.

Source: wikimedia commons

A brief economic recession in 1946 and 1947 sparked fears among many Americans of a return to the conditions of the Great Depression. But sustained stagnation never materialized. This was in part due to the G.I. Bill, which allocated $15 billion to help ease the economic reintegration of 15 million returning servicemen. By most accounts, it worked by allowing servicemen to acquire new skills through education, and by cutting down on competition for jobs that could have strangled economic growth. And as World War II transitioned almost seamlessly into the cold war with the Soviet Union, America's colossal defense budget supported a huge defense production sector, and helped buoy the economy as a whole.

After 1947, economic indicators rose across the board. The unemployment rate hovered at a paltry four percent. The middle class expanded, and with gusto--by the mid-fifties, almost two-thirds of American families were able to count themselves middle class. Salaries climbed. Americans cashed in their war savings bonds and bought the things they couldn't under wartime rationing strictures. An invigorated advertising sector helped turn the American economic landscape into one dominated by consumerism instead of investment. Among the products Americans bought was fiction, newly packaged to take part in the postwar mass marketplace. The hardcover book and the magazine were hardly extinct--but they were compelled to make room for the paperback.

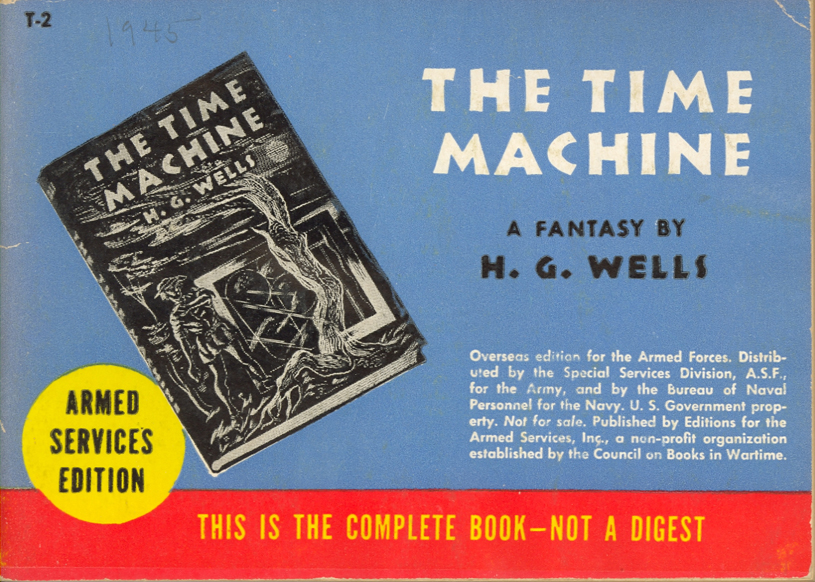

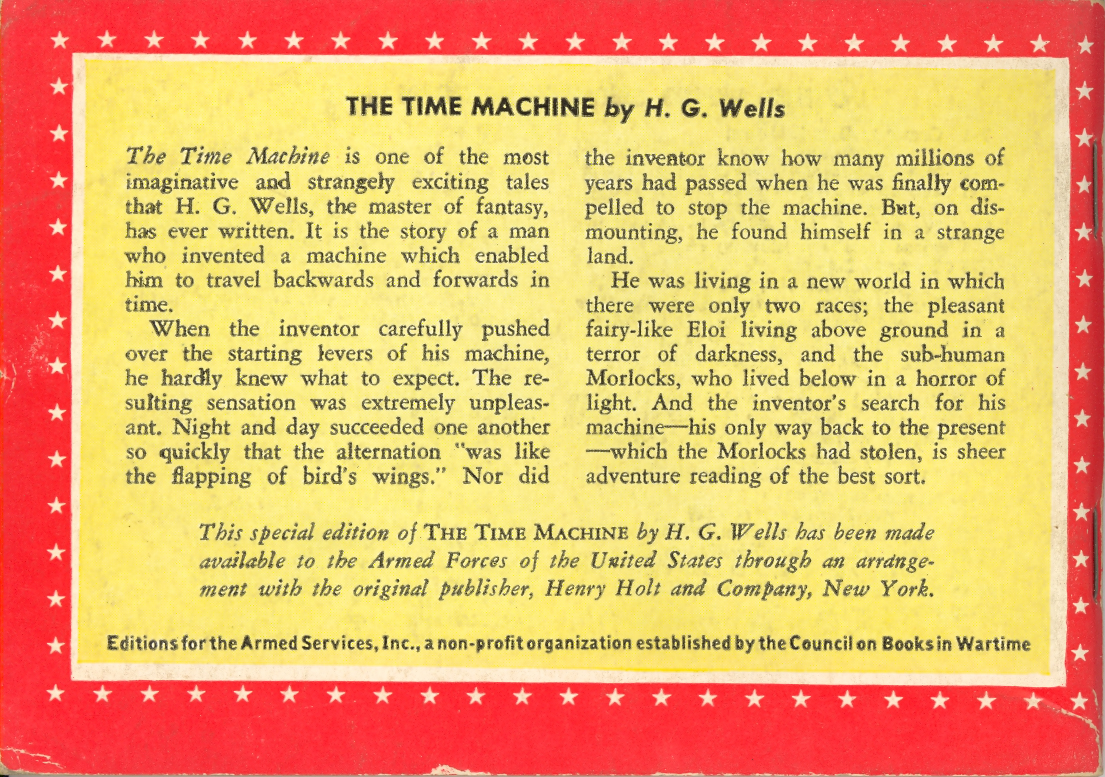

Courtesy of Amherst College Special Collections.

World War II was serendipitous for the fledgling paperback publishing industry. Wartime conditions on the home front discouraged other costlier kinds of entertainment, especially films. More important still was the Council on Books in Wartime (whose motto was "books are weapons in the war of ideas), which created a line of paperback books called the Armed Services Editions. The ASEs, distributed free to servicemen from 1943 to 1946, were cheaply printed and bound. They fit neatly into a serviceman's cargo pocket, a feat impossible for most hard-bound books. The armed services' appetite for these books was voracious: around 123 million copies of more than 1,300 titles were printed, distributed and read in the three short years of the operation of the Council on Books in Wartime. And in fact, each book almost always served more than just one man. Servicemen often ripped the books in half, so that two people could read at the same time, then swap at the halfway mark. The startling success of the ASEs primed American publishing houses for the postwar years by demonstrating that a vast untapped market existed for cheap paperbacks. Perhaps just as important, the ASEs socialized servicemen (and Americans generally) to the idea and form of the paperback book.