Science fiction had roots much deeper than the 1940s. Understanding the genre's origins is crucial to understanding its trajectory in the first decades of the cold war. But nailing down when and how science fiction began is a slippery prospect.

Nevertheless, we can identify some obvious antecedents to the science fiction that rose to prominence in cold war America. These works established the ideas that would make the genre so relevant to American readers from the late 1940s through the 1960s.

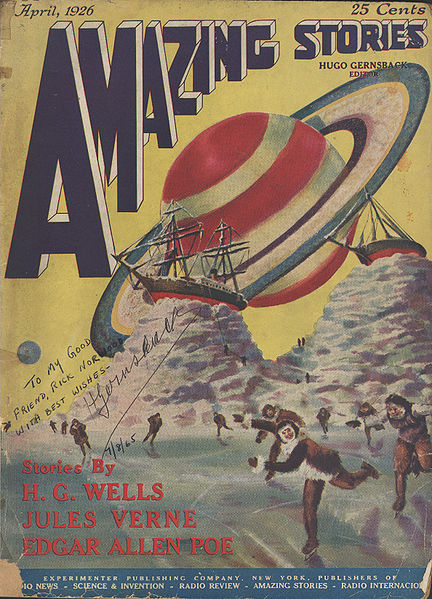

A string of nineteenth and early twentieth century authors perfected literary forms that were crucial to the development of American science fiction. In 1818, the tortured monster in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein prefigured both the horror and the profound alienation the scientific world view can produce. Beginning in 1863, Jules Verne published his voyages extraordinaires. In the UK, H. G. Wells penned a series of "scientific romances" that were markedly darker than Verne's stories in their implications about science for the modern world. The theme of science as a powerful but potentially malevolent force would have special resonance in the cold war, three quarters of a century later. On the American literary scene, writers like Edgar Allen Poe and H.P. Lovecraft wrote about the macabre and the weird, familiarizing American readers with the fantastical possibilities that would animate science fiction in later decades.

The genre as Americans would come to know it really began in 1926, in the cramped office of an immigrant from Luxembourg named Hugo Gernsback. A lifelong tinkerer and inventor, Gernsback was actually father to a torrent of science-themed magazines in the mid-twentieth century. Most of these weren't fiction at all but were devoted to popularizing technological advances in fields like electrics and radio. From about 1911 to 1923, Gernsback published mostly technical magazines for specialist audiences, before he began introducing the elements of speculation and extrapolation into the stories he wrote and bought. Paperbacks were virtually unknown to most readers in this era, and hard-bound books were too expensive for most Americans to purchase on anything like a regular basis. The magazine was king.

Source: wikimedia commons

The Gernsback magazine with the most historical relevance was Amazing Stories. Gernsback distributed the first issue, which featured stories by Wells, Verne, and Poe, in April 1926. The cover art by Frank R. Paul (now a recognized father of the science fiction's visual aesthetic) depicted men on ice skates fleeing two tall-masted sailing ships marooned on treacherous ice mountains on some hostile world, while a colossal Saturn-like planet loomed low on the horizon. Gernsback called the science-and-adventure themed writing he published scientifiction, and it quickly found a devoted, if small, audience. Readers who picked up this first issue of Gernsback's magazine from a newsstand would immediately recognize the three authors' names on the cover. They would also recognize the form of the magazine detective story magazines and westerns had been staples of popular American print culture since the Street and Smith firm began selling Detective Story Magazine in 1915. Gernsback wagered that the cachet of Wells, Verne and Poe would seduce buyers, even as the fantastical cover art intrigued them. The magazine cost twenty-five cents, the usual rate for soft-cover serial publications. More often than not Gernsback chose garish or lurid cover art, because he knew he had to attract buyers' eyes as they passed the newsstands and kiosks that sold his magazine.

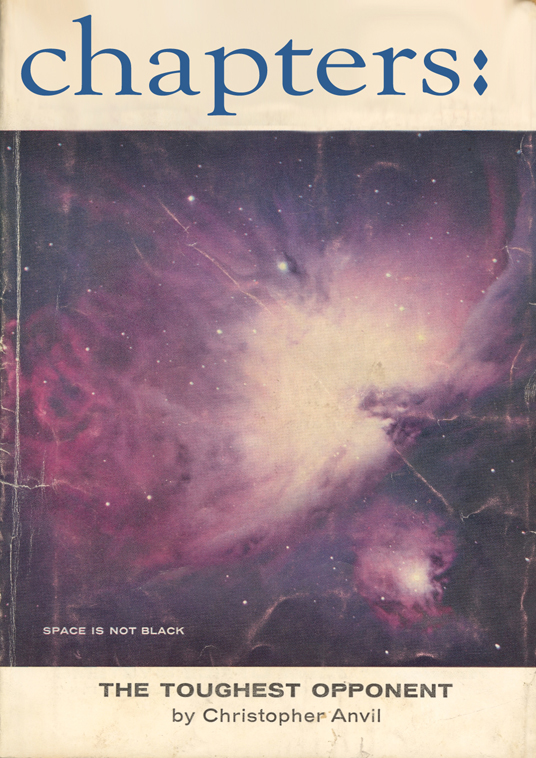

Amazing Stories sold steadily from the late 1920s until the Second World War, and its success prompted roughly a half-dozen more publishers to bring out their own science fiction magazines. Science fiction at this time was decidedly pulpy (works by heavyweights like Wells and Verne, when they were printed in hardcover book form, were marketed as scientific romances or classics, not science fiction.) There were not science fiction sections in booksellers' shops, and very few libraries stocked the magazines for lending. Instead, Americans bought their science fiction at bus depots and at Woolworth's counters, at kiosks on city corners next to daily papers and, sometimes, girlie magazines.

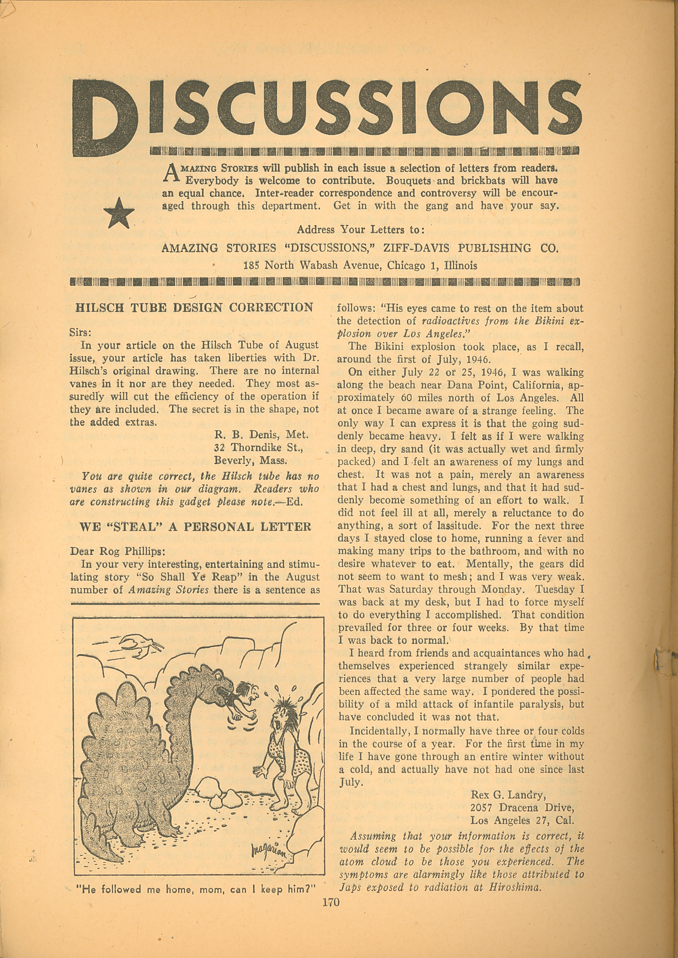

Courtesy of UMass SCUA.

As important as the genre's early form are the dynamics of its early readership. Gernsback incorporated a reader comments page into Amazing Stories, then took the unprecedented step of publishing readers' full names and addresses with their letters in his magazine. Fans of science fiction were probably always predisposed to seek each other out, but Gernsback made it easy. Then, shortly after he launched Amazing Stories, Gernsback founded the Science Fiction League, which provided a model for future clubs.

Science fiction fandom was unique in other ways, too. Fandom was intensely participatory. From the beginning there existed a relationship of reciprocity among editors, authors and readers. Many readers eventually turned pro, by publishing stories and building reputations as reliable authors. Fanzines were the norm, not an oddity, fans wrote their own fiction and distributed it among fellow fans. Conventions (called "cons" in fanspeak) soon sprang up, as fans and authors gathered to mingle and discuss the ideas of the genre. The devotion of science fiction's early followers, and their tendency to organize themselves, meant that science fiction survived the trials of its early years, including personality conflicts and serious material shortages during the war years.

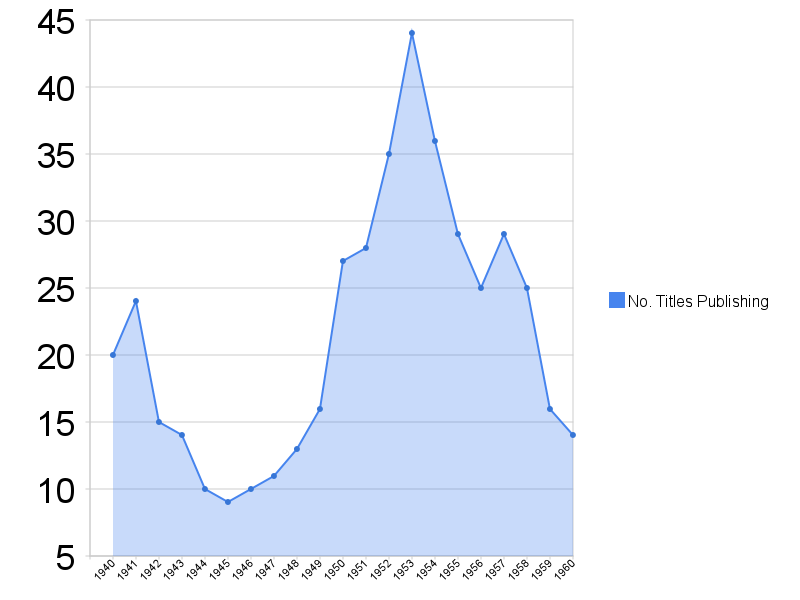

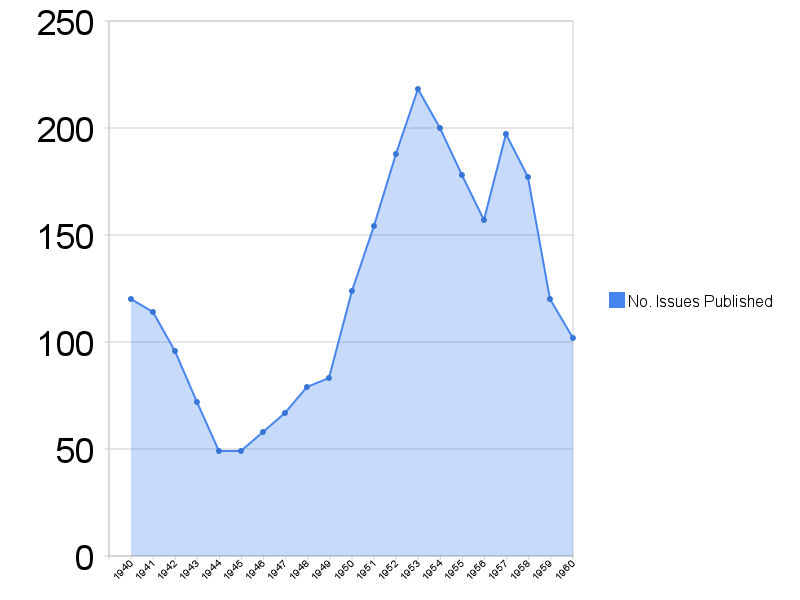

Science fiction's commercial success in these early days of the cold war was tangible, measurable in dollars and distribution charts. In 1945, there were fewer than ten magazines being published, and only about fifty issues were published that year. This had to do with wartime rationing and the displacement of huge numbers of Americans as well as the relative unpopularity of the genre. In fact, this was actually a drop from the numbers of magazines being published from 1926 until the start of WWII: the war sapped both supply and demand.

But business picked up when the war ended, and at the peak of the science fiction magazines' popularity in 1953, the number of titles publishing had more than quadrupled to more than forty. All told the magazines put out more than 200 issues that year, a staggering spike. Again, this had to do with postwar prosperity and the end of rationing as well as the genre's increased relevance to the scary world of the cold war. After 1953, the popularity of the science fiction magazine dropped precipitously”but not for lack of interest in the genre. Instead, a new medium was ascendant: the paperback. And in the flush postwar economy, Americans were ready and eager to buy.

Data source: ISFDB; Compiled by Morgan Hubbard.

Data source: ISFDB; Compiled by Morgan Hubbard.