Race

White abolitionists objected to slavery, but they did not necessarily want to eliminate racial hierarchy. White Americans had a variety of economic and political motives for opposing slavery. Promoting racial equality was not one of them. E.D. Hudson did not share the prejudices of his peers, and regularly depended on Black abolitionists to advance his causes. Hudson wrote in his journal "I had learnt to appreciate men according to the complexion of their hearts and not their skins - that many white skins had hearts blacker than the skins of any black man."1 Hudson consistently denounced church segregation and also proposed starting an integrated school in Connecticut.2 His papers further demonstrate the centrality of Black abolitionists to the planning and execution of the anti-slavery movement.

In his 1839-40 journal, Hudson maintained a list of contacts who offered him assistance on his various lecture tours. These people provided Hudson with the necessary logistical support to complete his journeys. Among the list included three Black men: Rev. Charles Gardner of Philadelphia, Nathan Blount, a preacher from Poughkeepsie, New York, and John T. Hilton of Boston. Hudson wrote of Hilton "Has the crime of having a dark skin."3 During a tour in 1842, Hudson took shelter in Augusta, Maine, with John T. Carter, who Hudson described as "a colored man - the only decent abolitionist."4 By sheltering Hudson, these men jeopardized their own tentative freedom and safety. Without such sacrifices, Hudson and other field agents could not have survived the vicious weather and brutal violence that plagued their tours.

Black Americans mobilized anti-slavery field agents, but they also actively spoke out against their own persecution. In 1841, Hudson partnered with the fugitive slave James L. Smith, who had escaped from slavery in Northumberland, Virginia. The pair endured constant abuse as they traveled together on a lecture tour through Connecticut and Massachusetts. Smith later commented on their difficulties in his autobiography writing "We had some opposition to contend with; it made it much better for the Doctor in having me with him. Brickbats and rotten eggs were very common in those days; an antislavery lecturer was often showered by them. Slavery at this time had a great many friends."5 Smith helped Hudson with the physical problem of mob violence, but also with the intellectual challenge of reaching a skeptical audience. As a former slave, Smith could articulate knowledge inaccessible to Hudson. In Torringford, Hudson struggled to engage a segregated congregation, but Smith persuaded them by speaking first-hand of slavery's horrors.6 Smith's actions offered a stronger critique of slavery than any words Hudson could produce. Smith put a human face on Hudson's polemics, and legitimized the doctor's radical stances. The anti-slavery movement did not begin with white activists like Hudson, but instead with Black Americans like Smith who rejected their servitude.

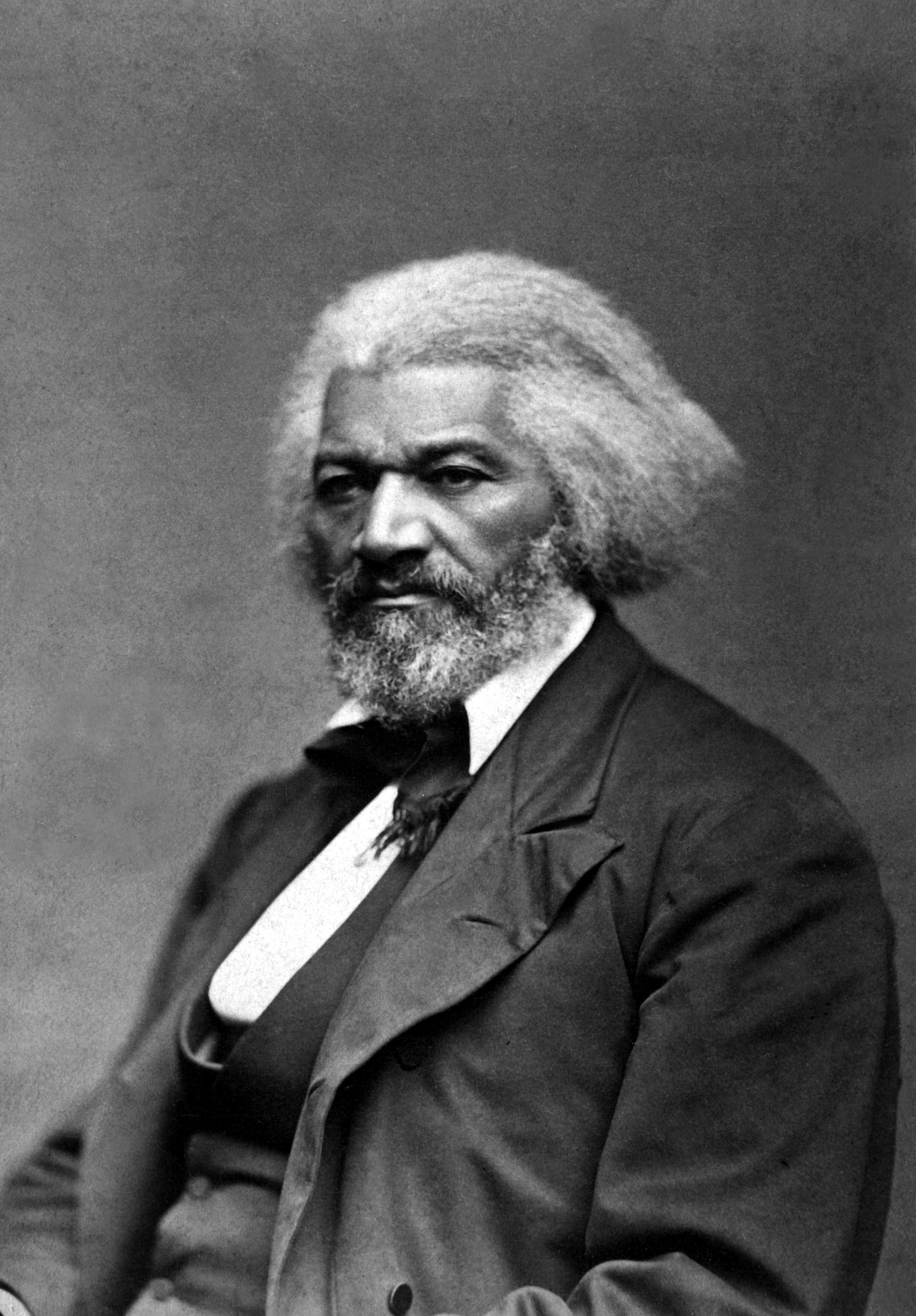

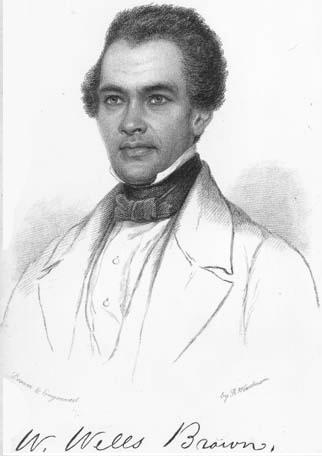

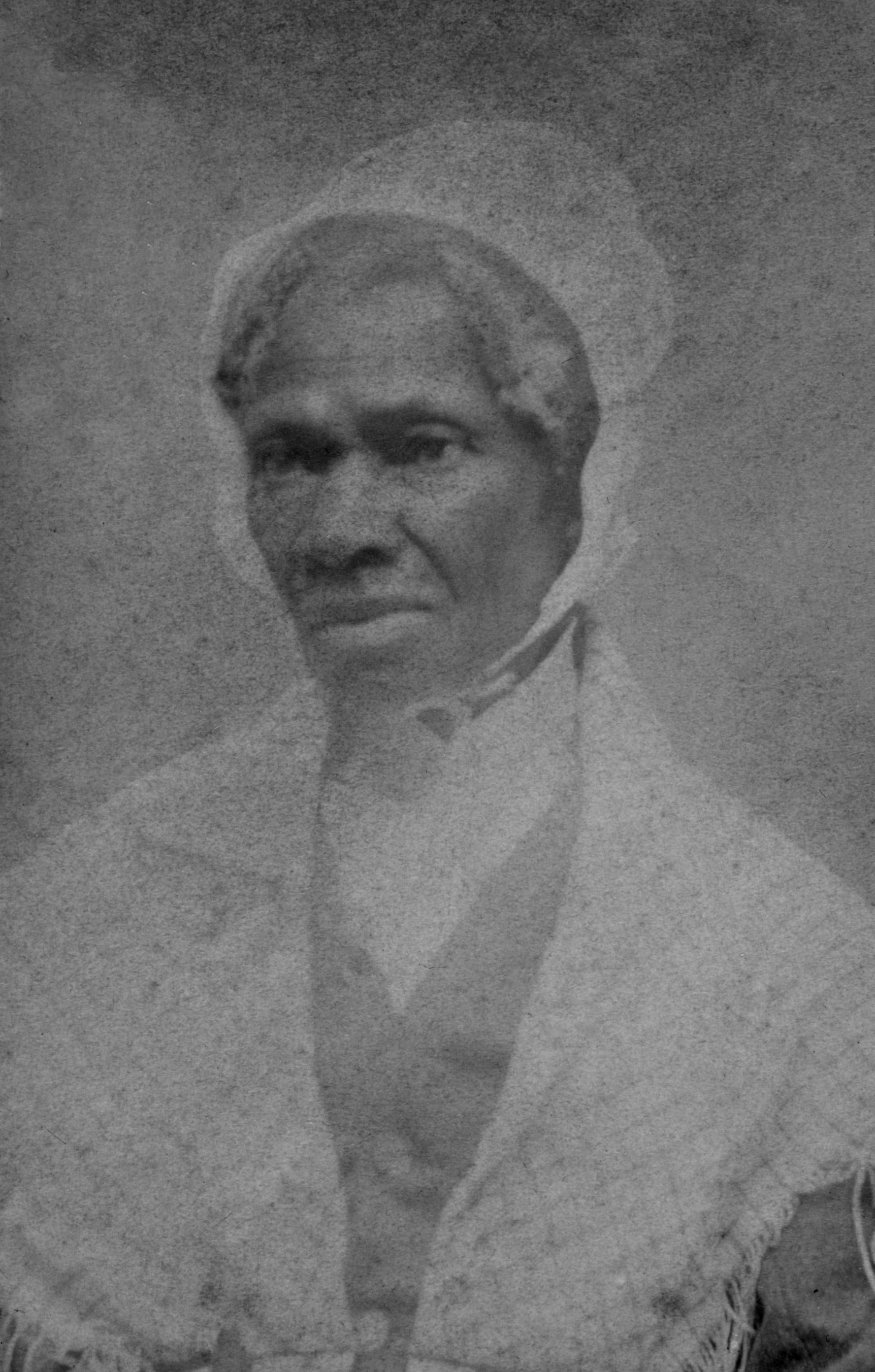

After his tour with Smith, Hudson continued to work with and learn from former slaves. During the late summer of 1842, Hudson traveled with the illustrious Frederick Douglass, Abby Kelley, Laura Bayle, John A. Collins, Jacob Ferris, Samuel Blakesley, and James C. Fuller on an abolitionist lecture tour through Upstate New York. In a letter to his wife Martha, Hudson commented that the team had a "strong pull" despite considerable pro-slavery sentiment in Seneca County and mob violence in Waterloo.7 Hudson and Douglass remained friends and continued to correspond well after the end of slavery.8 In 1847, Hudson partnered with the famous author and former slave William Wells Brown on another lecture tour through up-state New York.9 Hudson also had close connections to women of color. Through his involvement with the Northampton Association, Hudson formed a personal relationship with Sojourner Truth, and encouraged his son Daniel to follow her intellectual example.10

Despite white prejudices, Black Americans assumed the lead in initiating their own emancipation. Fugitve slaves and Free Blacks contributed to the abolition movement by offering practical, rhetorical, and intellectual support. Their lives presented the ultimate refuation of slavery.

Citations

Images: