Non-resistance

Beginning in the late 1830's, supporters of immediate abolition increasingly adopted the ideals of non-resistance, which rejected the use of force in favor of moral suasion. Non-resistants did not simply renounce violent acts, but instead repudiated all institutions that gained authority through violence. These institutions included the American government and Christian church. Non-resistants viewed the American constitution as fundamentally corrupt, and abstained from participating in the political process. Non-resistance arose from Christian philosophy, but Non-resistants viewed the church as irreparably tainted with violence. By disengaging from politics and the church, Non-resistance abolitionists alienated themselves from political and evangelical abolitionists.1 By disavowing violence, non-resistants also invalidated one of the primary weapons in the slaveholder's arsenal. Slavery gained power through violence so Non-resistants discredited violence to defeat slavery. Slave owners dispensed violence; Non-resistants deployed reason.

Hudson firmly embraced Non-resistance as an extension of his spirituality and opposition to slavery. On May 5, 1840, Hudson commented in his journal "a militia mustering today - contemptible and wicked! Men training to shoot, bayonet, and slaughter, their brother men, to make them do right, or punish them for doing wrong, when the very 'powers' that make the laws are lawless, cluching each other by the throats - ex the recent squabble on the floor of Congress by Mr. Byram of La. And Garland of Ala. - if men will not fear God and be governed by his commands, neither will they regard man - or his laws."2 Hudson opposed all forms of violence, which he viewed as incompatible with God's will. The state employed violence so Hudson renounced the state. He wrote in his journal on November 3, 1840: "the principles of our government are antagonistical to the principles of the gospel."3 He expressed similar sentiments in a letter to Martha: "I will be a traitor to the laws of my country and to my country before I’ll be a traitor to the laws of God and to God.”4

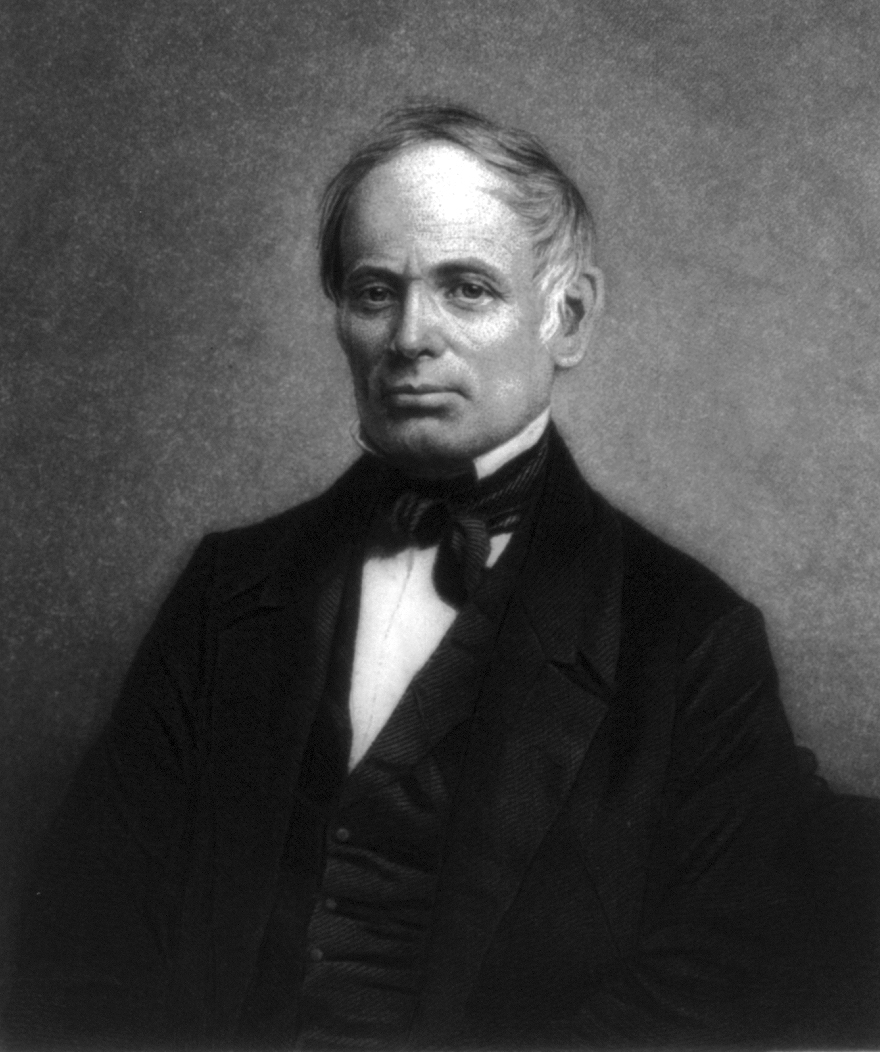

Non-resistance reinforced Hudson's spirituality, and commitment to human dignity. Hudson wrote in his 1840 journal "Inviolability of human life is the basis of non-resistance. Everything else pertaining to the question is a mere application of the principle, carrying it out!"5 In Hudson's view, Non-resistants could engage violent institutions so long as that engagement contributed to human rights. In a letter to fellow non-resistant Adin Ballou, Hudson argued that non-resistants could file for a writ of habeas corpus to free an enslaved person without violating the tenets of their belief.6 Non-resistants did not boycott violent institutions to promote anarchy, but instead condemned institutionalized violence to protect humanity. They concerned themselves primarily with reducing violence, not with eliminating organizations. Hudson's stances reveal that non-resistants still held spiritual beliefs and made political actions despite their aversion to the church and state.

Citations

Image: Adin Ballou, 1803-1890. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Digital ID: (b&w film copy neg.) cph 3b02632 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b02632. Engraving by H. W. Smith [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.